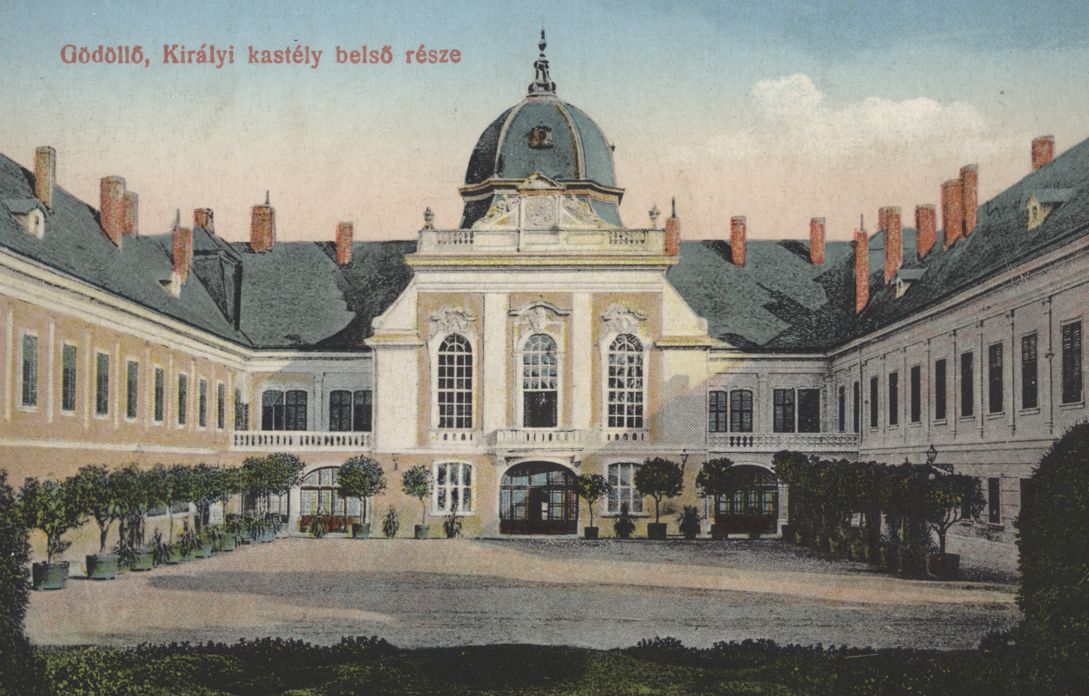

Antal Grassalkovich I acquired Gödöllô and the neighbouring settlements in a gradual fashion between 1723 and 1748. Gödöllô, situated in the valley of the Rákos brook and having favourable natural endowments, was chosen to be made the centre of this area that was now unified in Antal Grassalkovich I’s possession. Parallel to the construction of the palace, plans were drawn up to consciously develop the settlement on a large scale. As part of this project, Grassalkovich had a palace garden made, which was divided into an upper and a lower garden by the palace itself. The garden, which clearly represented elements of aristocratic taste, financial well-being and political power alike, was created in French style, with Versailles serving as a model for it. An outstandingly unique feature of this formal garden is that it had not been placed in front of the main facade but is a continuation of the inner court bordered by the wings of the palace. The court was made splendid by lemon, orange and bay trees.

The niche of the southern wing already had an operating small wall fountain in the time of Antal Grassalkovich I: the Baroque statue evokes an eventful scene with Heracles, a figure of Greek mythology, defeating the lion. The ornamental court, bordered by ballustrade, joined the upper garden by means of stairs. The upper garden had its end at about 440 metres (400 yards) from the building. The area between the rows of trees fringing the garden at both sides was divided by regular shaped flower beds. In the middle of the garden there was a fountain with formally-cut plants and a labyrinth behind.

In the north-western part, portraits of Hungarian rulers were displayed in the pavilion standing on the so-called Kinghill. Opposite this, a rifle-range for shooting had also been put up. The formal garden also had great reputation for its plants that came as rarity in Hungary as well as its statues inspired by mythology. The lower garden was also fragmented by straight, treelined roads so typical of the Baroque landscape architecture. The vegetable-garden, the game park and the pheasantry were also created here.

Bowing to the predominant trends of the age, the French garden was converted into an English, or in other words, a landscape garden towards the beginning of the 19th century by Antal Grassalkovich III (1771–1841) and his wife Leopoldina Esterházy (1776–1868). The stone fencing located at the back end of the upper garden had been taken down so that the size of the park could be enlarged. Certain elements of the garden had been left intact (among them the line of horse-chestnut trees, the Kinghill and the rifle-range), however, this newly-created park gave way to expressions and feelings of romanticism and sentimentalism rather than to the noble display of the older one. The park now became a finely-struck combination of gorgeous flower-beds sporting most extraordinary flowersand groups of trees found in a softlyarching system of paths. By ponding up the Rákos brook, two swan-ponds had been formed in 1817. The year 1837 brought along the construction of another orange-house, which further expanded the northern wing of the palace.

Bowing to the predominant trends of the age, the French garden was converted into an English, or in other words, a landscape garden towards the beginning of the 19th century by Antal Grassalkovich III (1771–1841) and his wife Leopoldina Esterházy (1776–1868). The stone fencing located at the back end of the upper garden had been taken down so that the size of the park could be enlarged. Certain elements of the garden had been left intact (among them the line of horse-chestnut trees, the Kinghill and the rifle-range), however, this newly-created park gave way to expressions and feelings of romanticism and sentimentalism rather than to the noble display of the older one. The park now became a finely-struck combination of gorgeous flower-beds sporting most extraordinary flowersand groups of trees found in a softlyarching system of paths. By ponding up the Rákos brook, two swan-ponds had been formed in 1817. The year 1837 brought along the construction of another orange-house, which further expanded the northern wing of the palace.

Following the extinction of the Grassalkovich family’s male line (1841), the property was sequestered for a period of 9 years. Military action in the 1848–49 freedom fight presented major abuses to the palace with the orange trees having been burnt, the fencing being wholly demolished and the stock of game dispersing.

After two interim owners, the palace and the domain were finally purchased by the Hungarian state in 1867. The state let free use of the palace and the park for Francis Joseph I (1830–1916) and Queen Elizabeth (1837–1898) as a coronation present. The small  fore-courts in front of the main facade were intended for personal use by the king and the queen. Both fore-courts had a fringe of trees of lush foliage. The fore-court used by the king served as the scene for his daily walks. Its appearance was much simpler and less colourful than that of the Queen’s fore-court, in which the favourite flowers of the queen were planted (violets and sweet violets). A small wooden porch had been built outside the queen’s ground-floor rooms with exit to the garden. This is where the small wooden corridor started, through which it was possible for Elizabeth to get to the ridinghall in bad weather.

fore-courts in front of the main facade were intended for personal use by the king and the queen. Both fore-courts had a fringe of trees of lush foliage. The fore-court used by the king served as the scene for his daily walks. Its appearance was much simpler and less colourful than that of the Queen’s fore-court, in which the favourite flowers of the queen were planted (violets and sweet violets). A small wooden porch had been built outside the queen’s ground-floor rooms with exit to the garden. This is where the small wooden corridor started, through which it was possible for Elizabeth to get to the ridinghall in bad weather.

The ornamental court of the palace thanked its lovely atmosphere to a number of orange trees and yuccas. The landscape garden characteristics of the upper garden had been preserved all along.

The so-called Reservé-garden (plant-starting garden) had been established south of the line of horse-chestnut trees, where in 1870 a palm-house, and then later, in 1895 a greenhouse was built. This was where the plants intended to be planted in the park were grown. In the south-western corner of the garden a nursery-garden was operating. At the end of the line of horse-chestnut trees, there stood a richly-ornamented wooden pavilion and the rifle-range renewed in 1875 was also there. In front of the orange-house, a skittlealley was to be found. When the royal family resided at the palace, the park was closed for the public, otherwise it was free to visit it in the given opening hours.

The lower park was split into two by the northern railway line that was routed in this direction as a result of the ruler’s residence being situated here. The two swan-ponds at the front façade were banked up in 1873 and 1894. The pheasantry and the game park were kept due to the royal hunts. The lower park, which was still surrounded by a fence, was free to use for the public.

After World War I, the palace became the resting-residence of governor Miklós Horthy (1868–1957). Only minor changes were applied to the landscape garden in this period (1920–1944). In the fore-court that once used to belong to the queen, an air-raid shelter was constructed. A circular fountain-pool of unreasonable proportions was added to the inner court. Farther down inside the park, they built a swimming pool with a small dressing-room that was in line with the end of the row of horsechestnut trees. Next to the major-domo’s building there used to be a tennis-court. From all of these, only the swimming pool is what still exists today.

The decades to come after World War II had witnessed a slow deterioration of the garden. New buildings (ware-houses, kindergarten) were put up in the neglected and weedy park, where a great number of out of place plants were planted. The rebirth of the park came with the reconstruction of the palace that gained momentum in 1994. This concerned mainly the 26.1-hectare upper park as the lower park is now a built-up public area.

The two fore-courts were reconstructed in 1998 and 2000 in accordance with how they used to be in the royal period. In the queen’s fore-court the protruding, visible part of the Horthy air-raid shelter was demolished at this time. The swimming pool, which was a remnant of the Horthy era, was also dismantled and the place was given ornamental flooring and balustrade. The upper park still preserves the structure of the English or landscape garden. It is characterised by trees one hundred years old or older. Among the most precious tree species are gingko, Wellingtonia trees, ashes, white limes, yew-trees, maples, white oaks and ordinary horse-chestnut trees.

In the back of the park there remained patches of grass that are inhabited by protected plant species such as thlaspi, centaurea and ranunculus. The area of the park has been cleansed of out-of place plants, nursing of affected trees has begun and young trees have been planted.

The fore-courts and the upper park were declared natural preserves in 1998. The reconstruction of the Kinghill pavilion was completed in 2004. A 5.2 hectare area of the upper park was renewed in 2010 as a romantic landscape garden.